Big native vegetation losses halted in South Australia by 1985 law – after around 75% of land already cleared

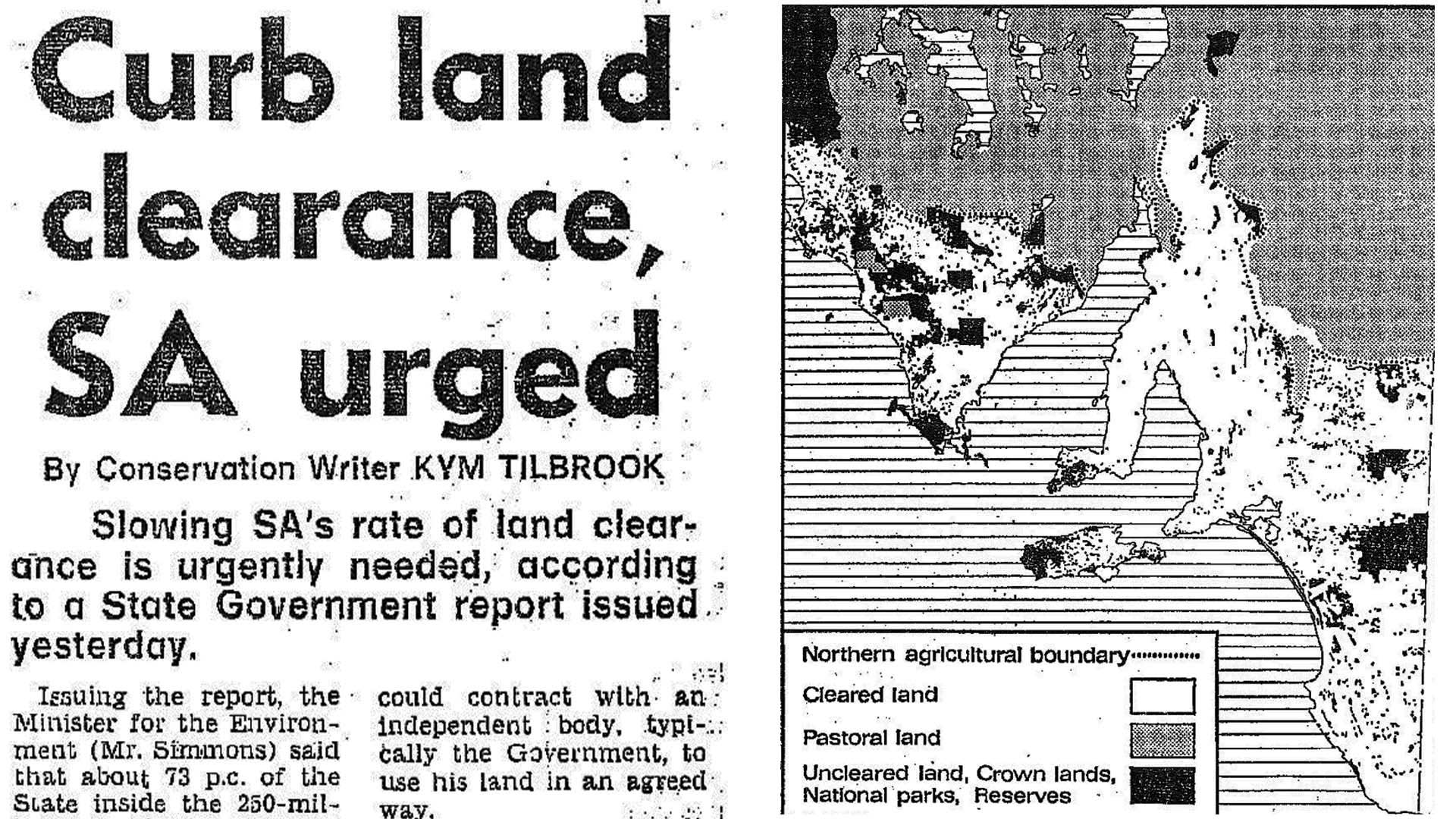

Conservation writer Kym Tilbrook highlights on a front page of The Advertiser, Adelaide, the government inter-agency enquiry 1977 report showing that nearly 75% of native vegetation in South Australia's agricultural areas had been cleared.

The Native Vegetation Management Act 1985 was South Australia’s first big brake on land clearing in the state – but after nearly 75% of the state inside the 250-millimetre rainfall line had lost native vegetation.

Steele Hall’s Liberal state government responded to local and global environmental concerns in 1970 with a committee of inquiry. Its report, two years later, stimulated Don Dunstan’s Labor government to create the environment and conservation department in 1972.

From 1973, scientific and policy employees were added to national parks & wildlife, planning and museum staff in the new agency. Among its first major initiatives, the state government cabinet approved an inter-agency enquiry into native vegetation clearance. The committee’s report, documenting for the first time the extent of clearance throughout South Australia, was released to the community in 1977. After regional areas were consulted, a final report advised urgent action to slow the rate of clearance. But incentives were favoured, rather than regulatory constraints, on land clearing.

After legal and financial studies, David Tonkin’s Liberal government in 1980 introduced heritage agreements – legally binding between the crown and individual landholders to have privately-owned native vegetation of high conservation value managed to maintain or improve those values. The agreements were binding on subsequent landholders and, in return, financial incentives were provided, including dropping state and local government charges applied to the land, fencing costs and management assistance and advice.

The heritage agreement scheme was hailed around Australia as a first. Many landholders signed up but, over the next two years, monitoring by the Nature Conservation Society of South Australia confirmed it was largely conservation-minded landholders who committed to the heritage agreements. Farmers intent on more clearance show little interest in changing their plans and, if anything, the land clearance increased.

Faced with this and an electoral commitment to curb native vegetation clearance, John Bannon’s Labor government acted quickly in May 1983 with statutory controls on clearance, using Planning Act 1982 regulations. Conservation groups welcomed the move and, significantly, the state's peak farming body, the United Farmers & Stockowners, didn’t question the controls, focusing instead on compensation.

The government defended its decision not to pay compensation by saying it was looking to balance conservation and development, and that most landholders lodging applications received approval to clear around 40–60% of the area. But, with long delays in the assessments, farmers’ unrest built, ending in a test case and a high court of Australia ruling (5-4) in the landholders' favour.

To retain the controls, the government had to negotiate a political solution in parliament’s upper house, the Legislative Council. This saw the controls removed from the planning system and placed in the new Native Vegetation Management Act 1985, with compensation to be paid to landholders. Some landholders in marginal areas used the payments to restructure their businesses or, in some instances, to leave the industry and the political controversy waned.

In the following years, little broad-acre clearance was approved and almost $70 million paid in compensation. By the early 1990s, the government believed most bona-fide farmers had been compensated and it introduced the Native Vegetation Act 1991, with sunset clauses that ended compensation. Also ended was any further broad-acre clearance. The Act made it clear any approvals for clearance would only be given in exceptional circumstances or for individual trees.

Most other Australian states moved in the same general direction but many years behind the pioneering initiatives of South Australia.