George Milner Stephen's amazing rise to acting governor in early South Australia until land, perjury scandals hit

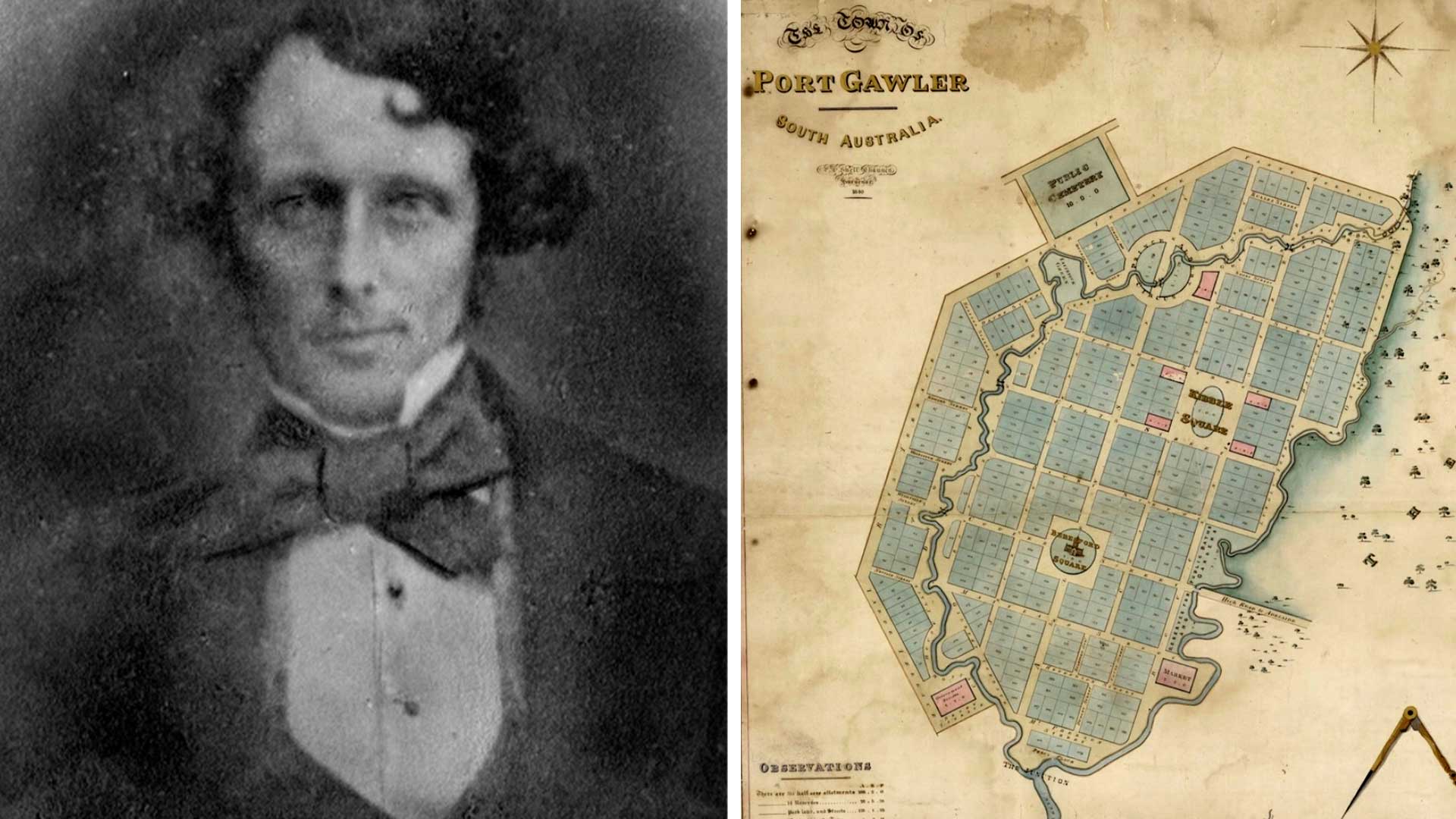

George Milner Stephen in 1841 and the map designed by South Australian surveyor Phillip Chauncy of Port Gawler with streets named after mariners, explorers and British royalty. The map was prepared for in 1939 for captains William Allen and John Ellis, major investors in the failed housing scheme prompted by Stephen. The town was never built and the map, never published, was restored by State Library of South Australia senior conservator Peter Zajicek for display in 2023.

Images courtesy State Library fo South Australia

George Milner Stephen had an amazing rise on the back of the feud between South Australia’s first governor John Hindmarsh and resident commissioner James Hurtle Fisher.

Not qualified beyond legal clerk, Stephen became the province’s advocate general and crown solicitor in 1838. Within months, when Hindmarsh was recalled to England, Stephen was acting governor. A brilliant school student from a well-connected English family (he was related to colonial office under secretary James Stephen), George Stephen arrived in 1829 in Hobart Town where his brother Alfred was crown solicitor. George Stephen became a supreme court clerk.

During 1837 in South Australia, Charles Mann resigned as advocate general and crown solicitor after siding with Fisher in the dispute with Hindmarsh. Hindmarsh, who heard from judge John Jeffcott that Alfred Stephen had resigned in Hobart as crown solicitor, wrote to Van Diemen’s Land governor John Franklin inviting “Mr Stephen” to accept the Adelaide post. Franklin was surprised to get George Stephen’s request for three months leave to visit Adelaide to consider the offer to him as crown solicitor, and a £100 advance to buy law books.

In 1838, George Stephen left amazed people in Hobart to soon become South Australia’s advocate general. Hindmarsh told the colonial office’s James Stephen that George Stephen’s “very connexion with yourself” justified the appointment. Stephen did study hard and drafted useful ordinances. He helped arrest several “dangerous Ruffians” and prosecuted them at the quarter sessions court where, with brother Alfred’s advice, he also won two civil actions and a chancery suit.

Since resident commissioner Fisher hadn’t been attending council of government meetings, when Hindmarsh sailed for England in 1838, George Stephen became the senior council member and thus acting governor. The colony’s treasury was empty and Fisher refused to pay the civil service from the land fund. Stephen loaned £200 from his own pocket to pay the police and he allotted country sections of land to settlers.

When governor George Gawler arrived, Stephen became colonial secretary and received 229 signatures praising his liberality and ability, though he blocked a protest meeting against his land speculation. The land speculation scandal, also involving Hindmarsh and his wife, ended Stephen’s rise.

Soon after arriving in South Australia, Stephen had bought 1,600 hectares of swampland 43 kilometres north of Adelaide next to the Gawler River. He promoted a big housing scheme, named Port Gawler, and sold half the land quickly before being accused of fraudulent speculation. It led to a high-profile defamation case against opposing newspapers: the Southern Australian and South Australian Gazette and Colonial Register.

After losing the last court case, Stephen resigned all public offices, sold more land for himself and Mrs Hindmarsh – and married one of her daughters, Mary, and sailed with her to England. He became secretary to John Hindmarsh as governor of Heligoland where he did portraits of European notables. Stephen applied to be admitted to the Middle Temple in London and was cleared by the colonial office in 1845 of Adelaide perjury accusations.

In 1846, Stephen returned to Adelaide but failed in bids to become advocate general and, later, chief justice. After gold was found in Victoria, Stephen claimed to have found a deposit near Adelaide. On a hot December 1851 day, a crowd with shovels and tin dishes climbed the range but neither Stephen nor his mine were found.

In Victoria and later New South Wales, Stephen had mixed success in law, mining and parliament. From 1877, he dabbled in spiritualism and faith healing. Paradoxically, he suffered badly himself from “an internal affliction” and died after an operation in 1894.