Adelaide turnaround to best infant mortality with milk control, end of horse transport and health cultural cringe

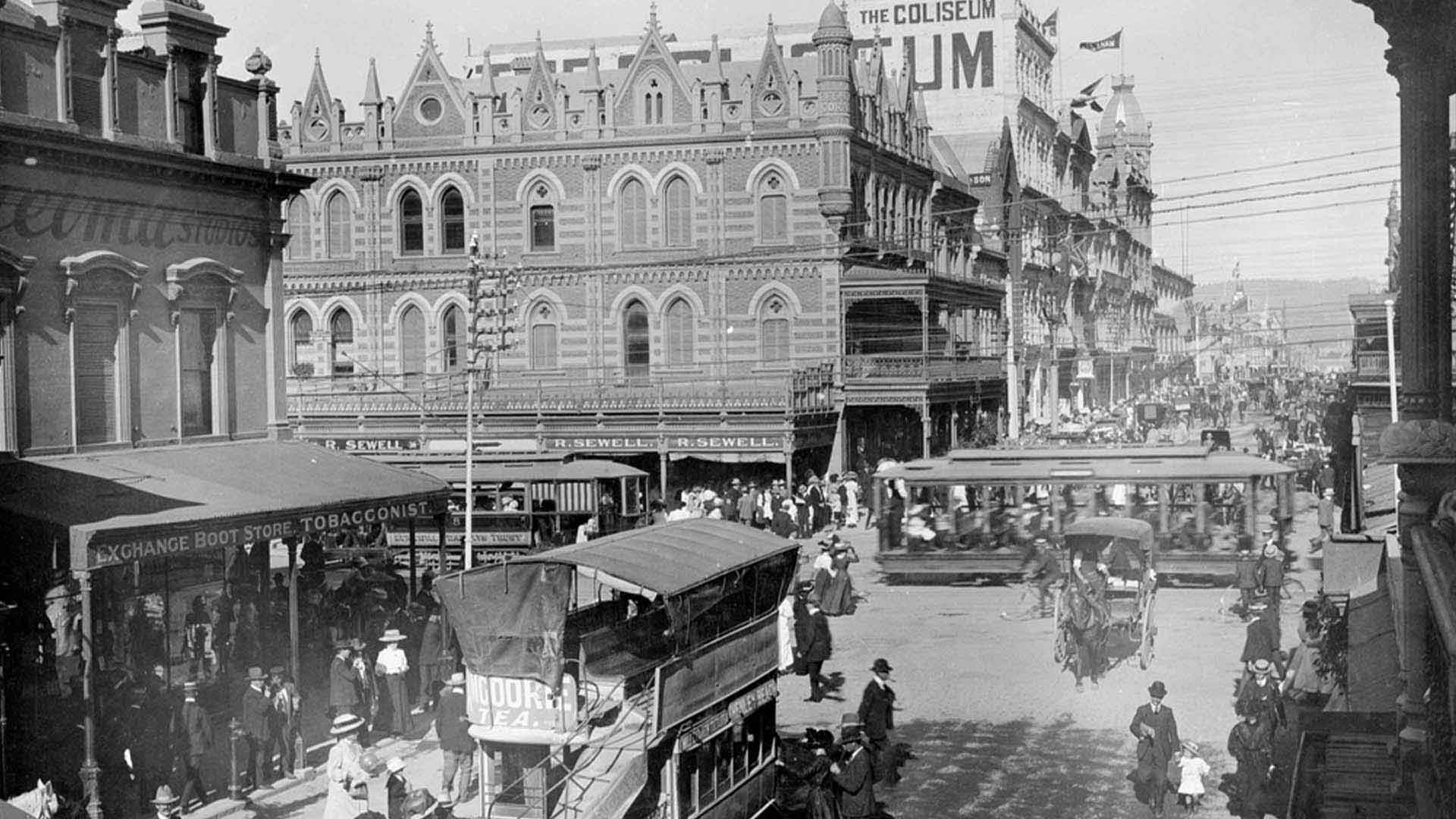

The start of the change from the health hazard dumped on Adelaide streets by horse transport is captured in this 1909 Beehive Corner scene looking east from Hindley Street, Adelaide, up Rundle Street, with horse trams and carriages still dominating but new electric trams passing on King William Street.

Image by Gabriel Francis, courtesy State Library of South Australia

Adelaide made a remarkable reversal from having one of the worst rates of infant mortality – peaking at 200 per 1000 babies annually in the 1880s-90s – to a 1910 decline to a rush downward in 1937 to 23 per 1,000 – the lowest in the western world.

Many significant public health advances came via bacteriologist and health officer Thomas Borthwick, who was behind South Australia Public Health Act of 1898 – with some of the strictest regulations anywhere in Australia – and a central board of health. Borthwick became a member of the new metropolitan dairies and abattoirs boards.

With inspections and licensing of vendors, he gave control over milk that had been a killer for the last 20 years of the 19th Century. Not only had it previously been produced by multiple cow keepers in dirty conditions but the milk was adulterated; either just diluted with water, or with chalk or even coal tar to improve its “creaminess”.

Milk left in metal churns to warm up on dusty city doorsteps was a perfect for incubating bacteria. Few mothers in the city bothered to boil the milk, so infants mostly died of dehydration from gastroenteritis.

A major technology change to electric trams and motors cars brought an end to transport relying on horses – and dropping 70 tonnes of excrement and urine daily on the streets – also eliminating the “aerial sewage” in dust from the Victorian-era streets. The city parklands also were shifting from being used as dumping grounds for rubbish and human sewage.

Mothers caught in wider social problems around poverty, contraception and abortion added to infant mortality. Police reports analysed by the historian Pat Sumerling showed dead babiess being found around late Victorian Adelaide: by the river, in the river, in the parklands, in backyard toilets. Baby farming involved a flat fee paid by a mother to a minder took the infant. Death would soon follow from neglect or outright murder.

The other factor in the turnaround in infant deaths was the end to what Peter Morton describes as the medico-cultural health cringe in colonial Adelaide. Victorian Adelaideans had been striving to recreate a genteel English town with English society, manners, language and habits all successfully transferred. This meant comparing Adelaide with Cheltenham or a Bournemouth rather than cities with the same hotter climates on the same latitude 34.5 degree from the equator.

Dr Edward Way, the city’s health officer in 1880, thought the primary cause of infant deaths was Adelaide’s hot summers that had a “direct prostrating effect upon the nerve centres”. Dr Sylvanus Magarey, the children's hospital resident doctor, saw the heat as causing “fluxionary hyperanaemia of the brain,” or, put simply, a rush of blood from the head when the sun heated the scalp.

But, until Borthwick, there was barely a link made between that heat being unsuitable, as the prime example, for milk being produced and delivered in a very English way according to English conditions.